Details

Gameplay Programmer

Narrative Designer

Level Designer

Design Lead/Producer

My Contributions

Need to know more?

Pick a topic to deep dive on

Work with the tools at hand

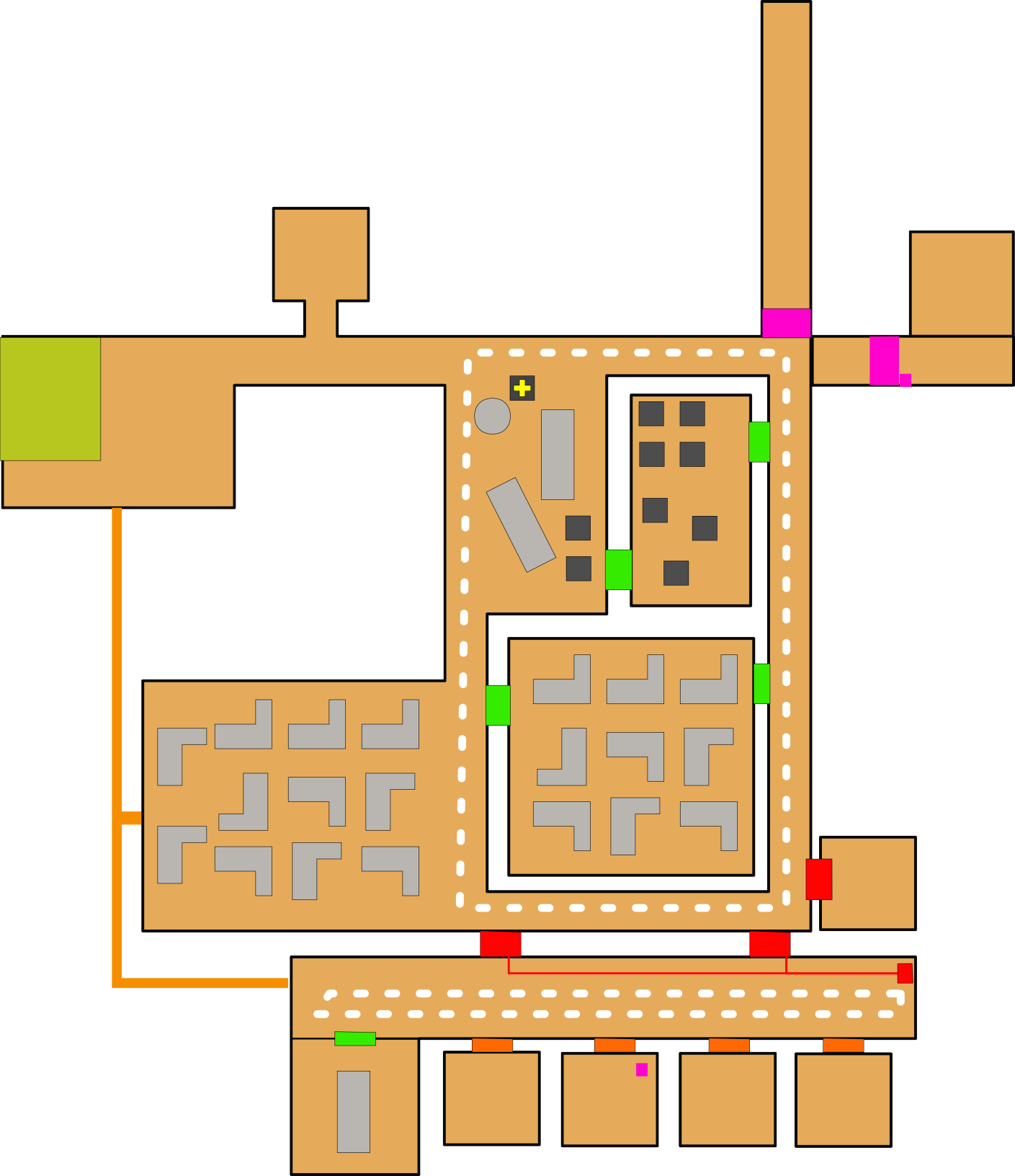

For the complexity of the story we wanted to tell, we were unable to record voice-overs or have animated cutscenes within the game. Both approaches were too labor intensive and could not easily be iterated on in response to feedback given the project timeline and the already high workload on the art team. Utilizing the command line terminal object already in the levels as a puzzle element, we could deliver the story to players through emails, personnel files, and workplace memos.

Every terminal belongs to a different user, allowing the player to read both their inbox and outbox. Every named character mentioned in an email also has an associated bio to provide additional context and hint at their place in the narrative. Through reading the time stamp, as well as seeing the environment surrounding any given terminal, the player can piece together the story of how this Antarctic research base fell to ruin.

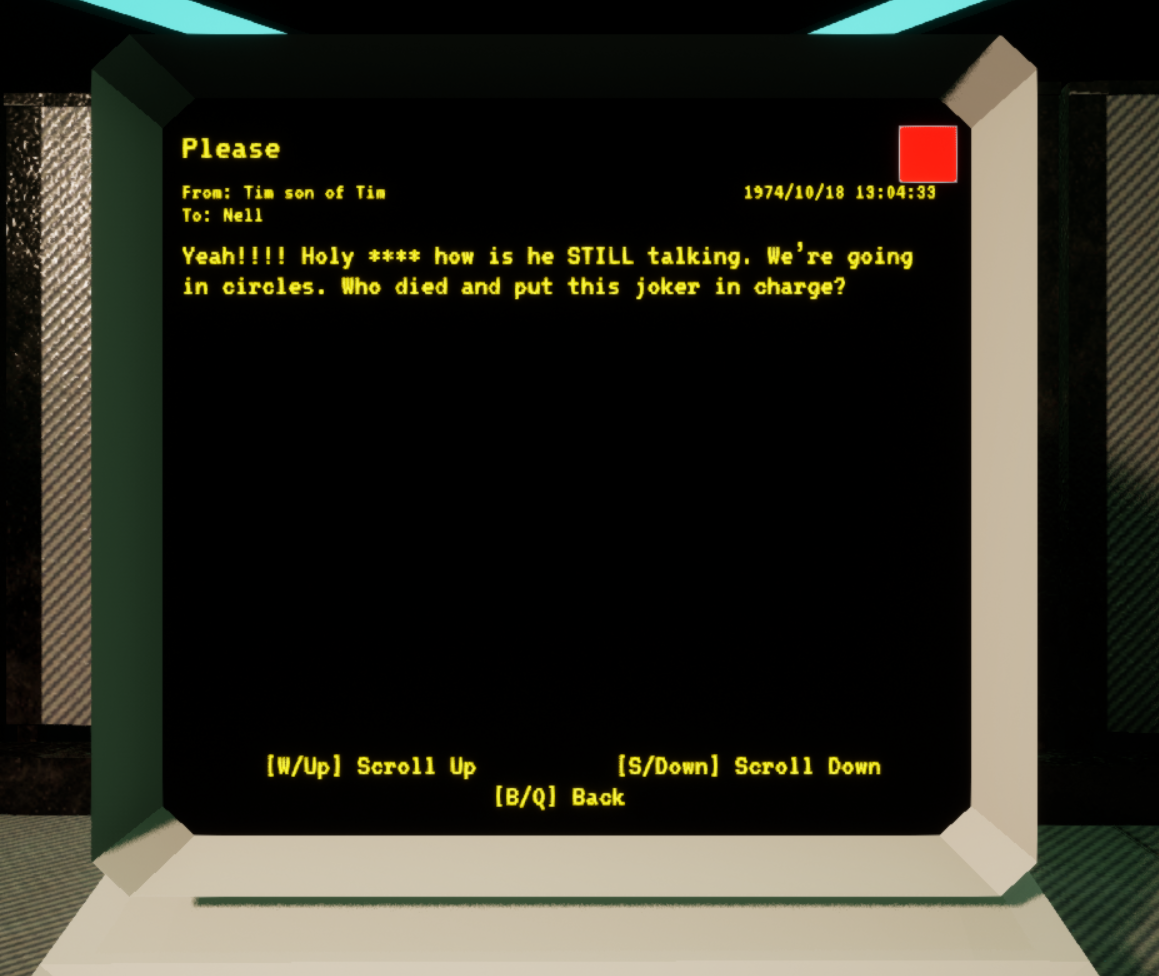

A terminal in use between the comedic character 'Tim, son of Tim' and the player character 'Nell'

Always have a clear plan

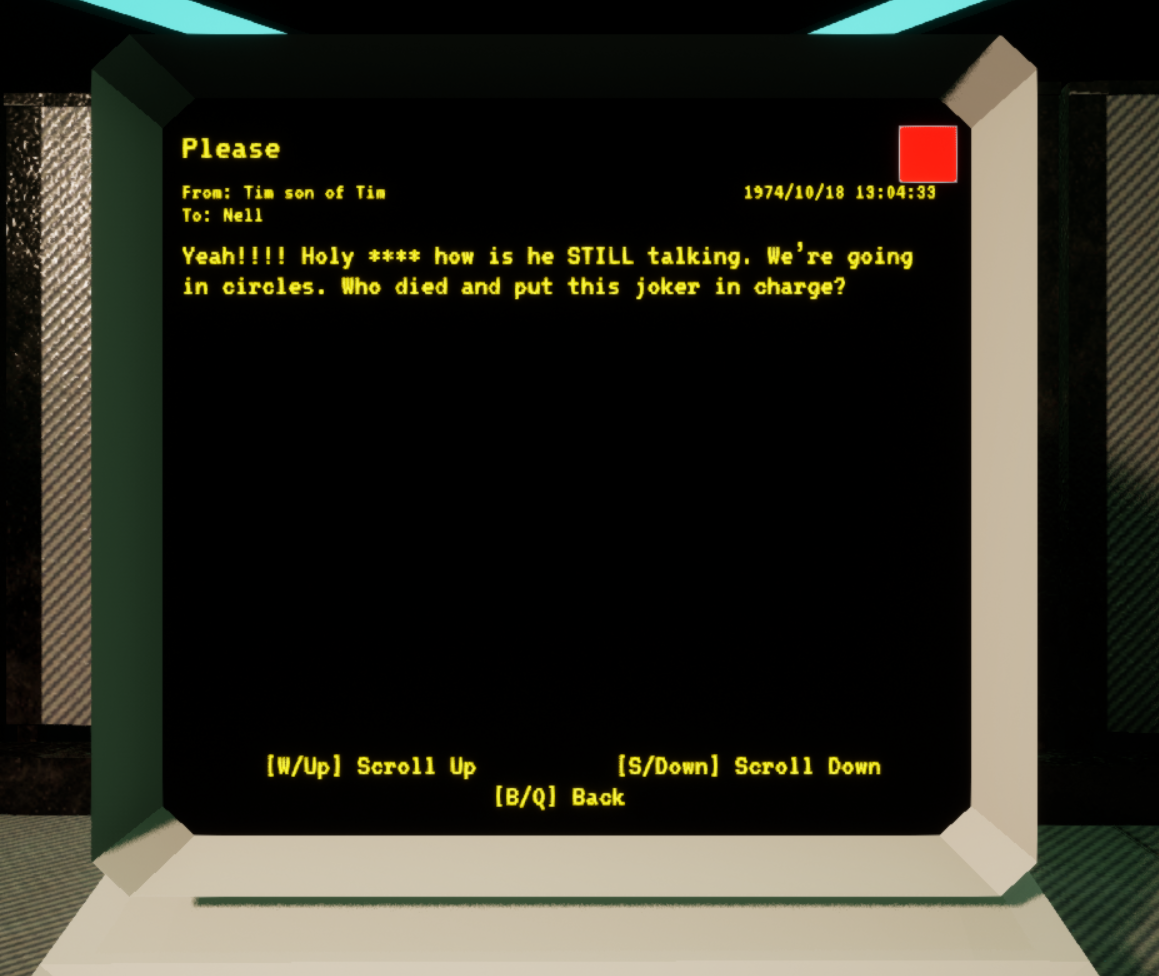

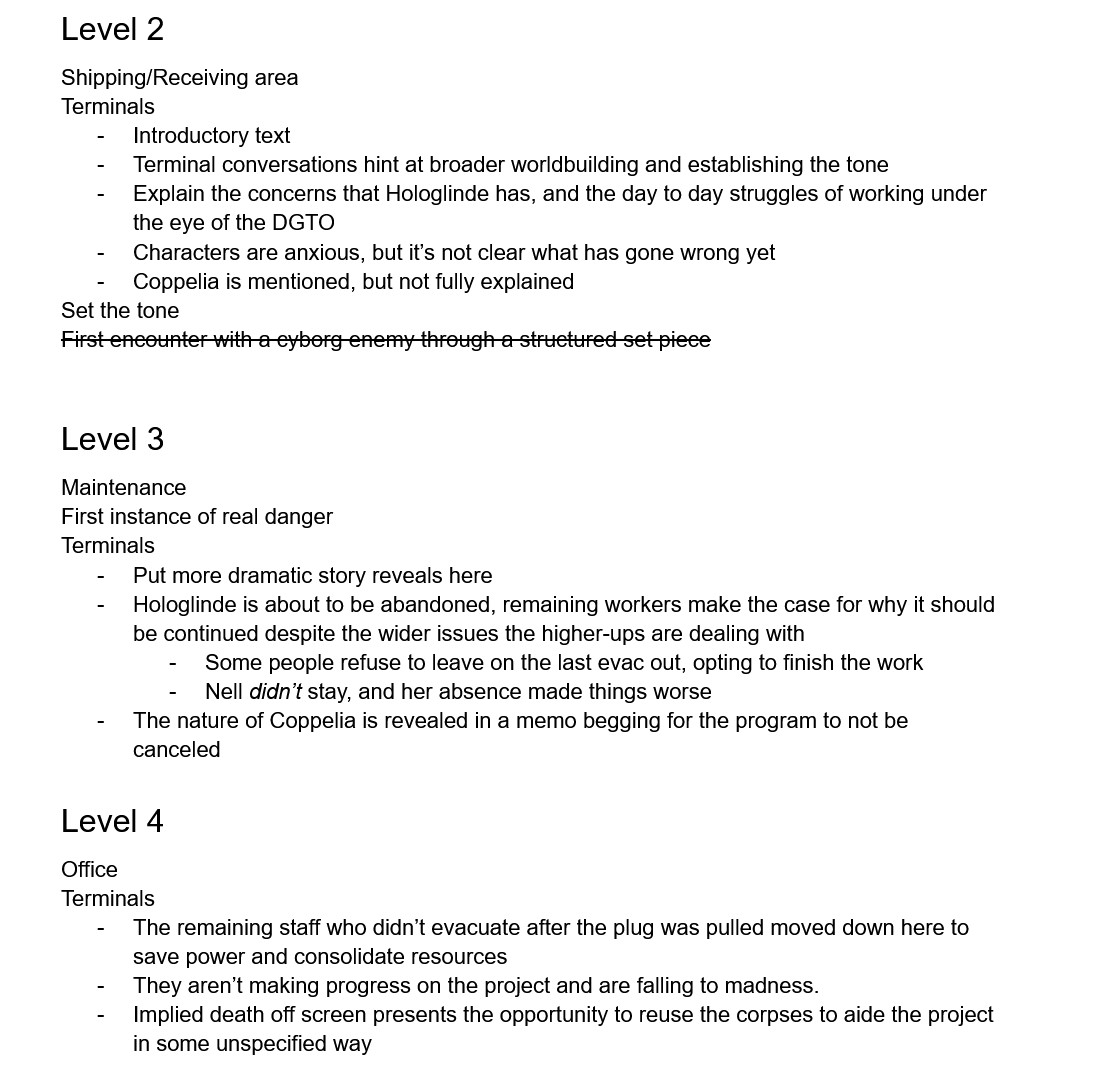

Before we put anything into the engine we made sure we had a rock solid outline. Working collaboratively with the rest of the narrative team, I wrote an outline and timeline of events and tied them to specific dates so that the timestamps on the emails could line up. I wrote the majority of the emails and personnel files, though using this system we were able to keep all contributors consistent to the tone and events of the game.

Next, I broke up the story into a set of narrative beats and arranged them in order from each level. This kept the team in line tonally, and helped create a rising action and increase in tension across the game.

Lastly, every email and personnel file was written in the shared document first before making it into the game. Each entry contained which team member wrote it, a quick summary of what purpose in the narrative it served, and where in the game it was located. This allowed us to get feedback on the writing before implementing anything in game. When playtest feedback came in about a specific email we could cross reference its location to find it in the document and make the appropriate changes.

A screenshot from our lore bible we used to keep everyone on the narrative team on the same page

An example of our level by level beats

Keep it above board

Our team had to operate within strict content guidelines prescribed by the course instructors. Projects in the GAM300 class could not be anything above an "Everyone 10 and up" rating. Our team had a running joke of using Shadow the Hedgehog as our role model: if he didn't say or do it, then we couldn't put it in our game. These were difficult constraints to make a horror game within. Death and suffering had to be implied but not depicted. There could be no blood, no direct threats of violence, or even usage of the word "kill."

The grizzly fate of the station researchers, being turned into violent and maddened cyborgs, had to be depicted in a way that could still be scary without it being death. There are emails written from the perspective of staff members after being assimilated, showing that they are very much still alive even if they aren't well. Their crazed and confused writing speaks to a generalized suffering without mentioning any specific topics that would take us out of Shadow the Hedgehog territory.

Much like a haunted house attraction, the most powerful tool is implication. The terror has to exist in the player's head.

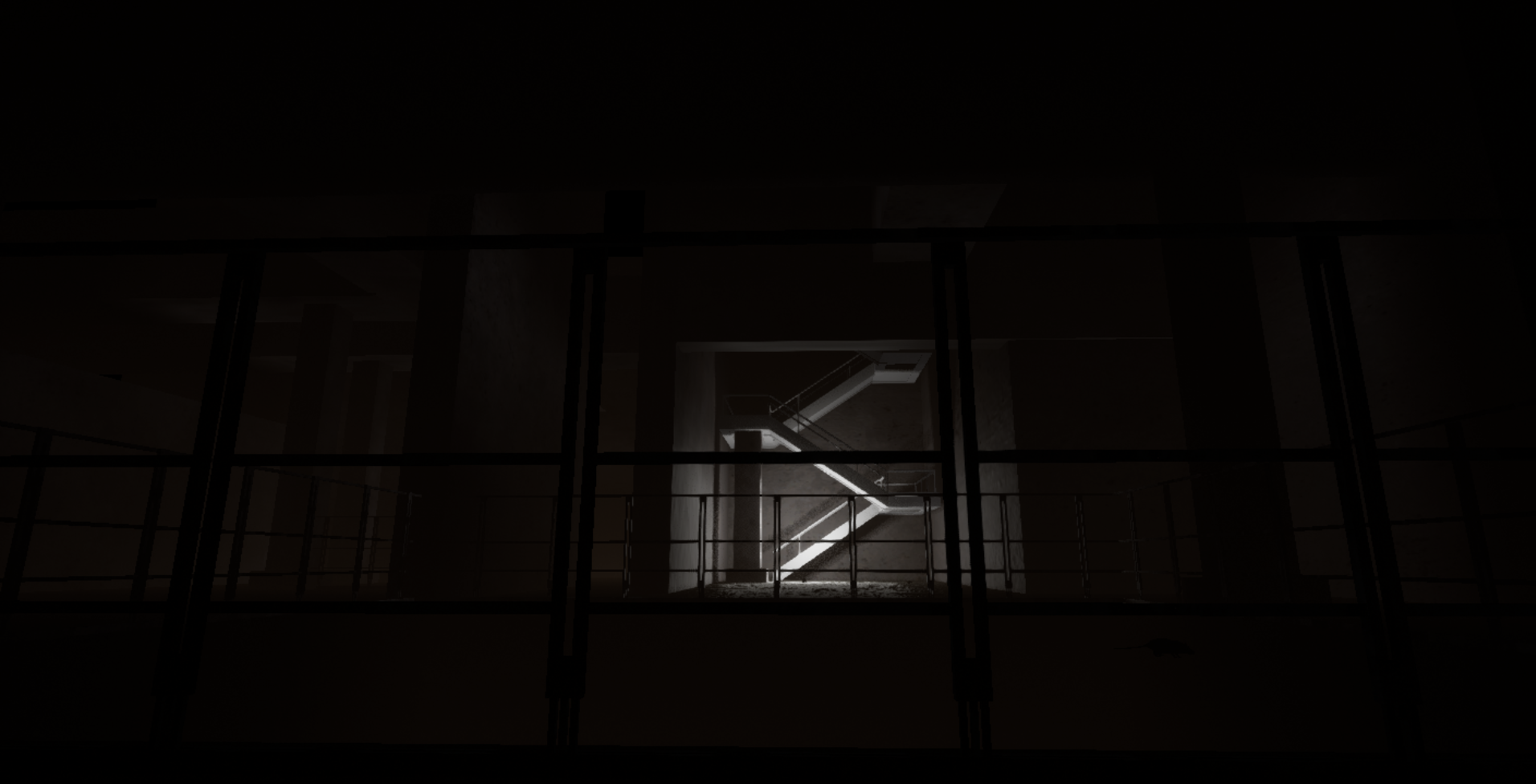

Dark environments can be scary: what could be hiding in the shadows? The hope was to give the player some very M rated fears using only E rated language

Draw it out first

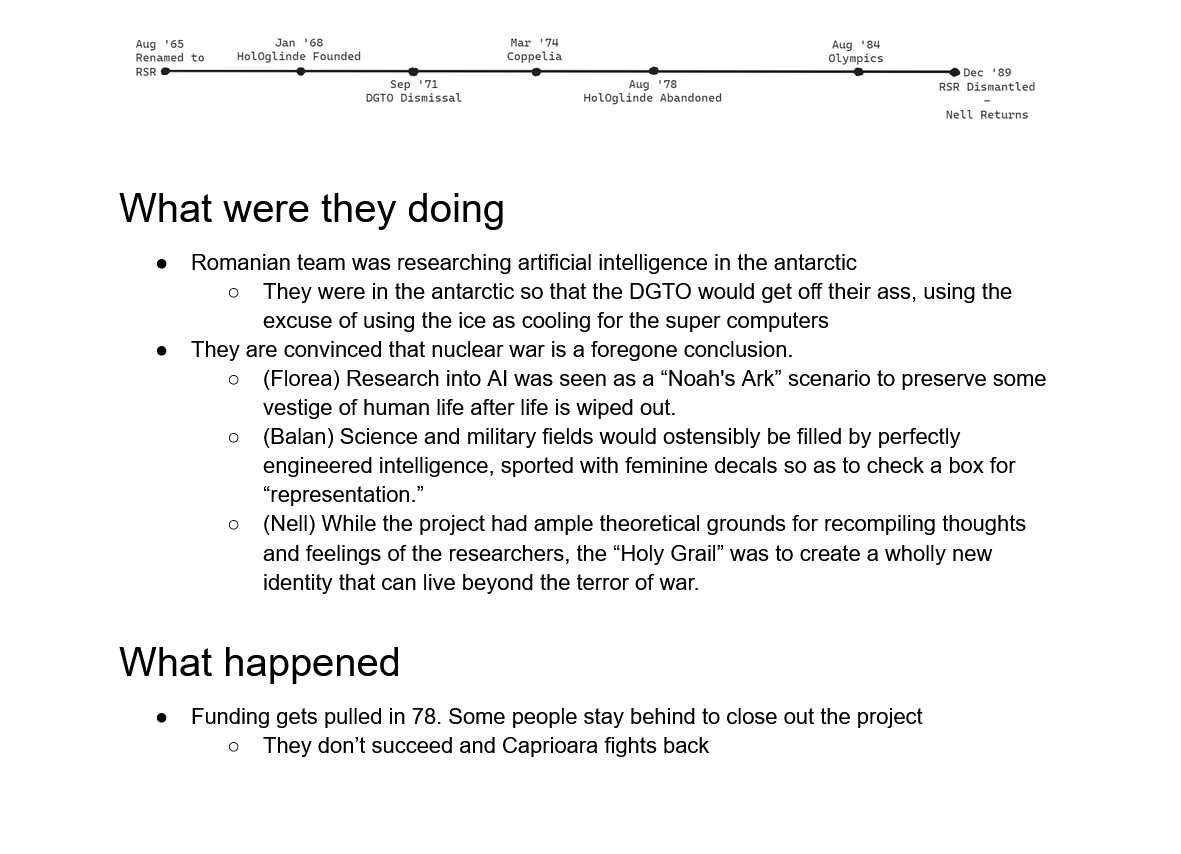

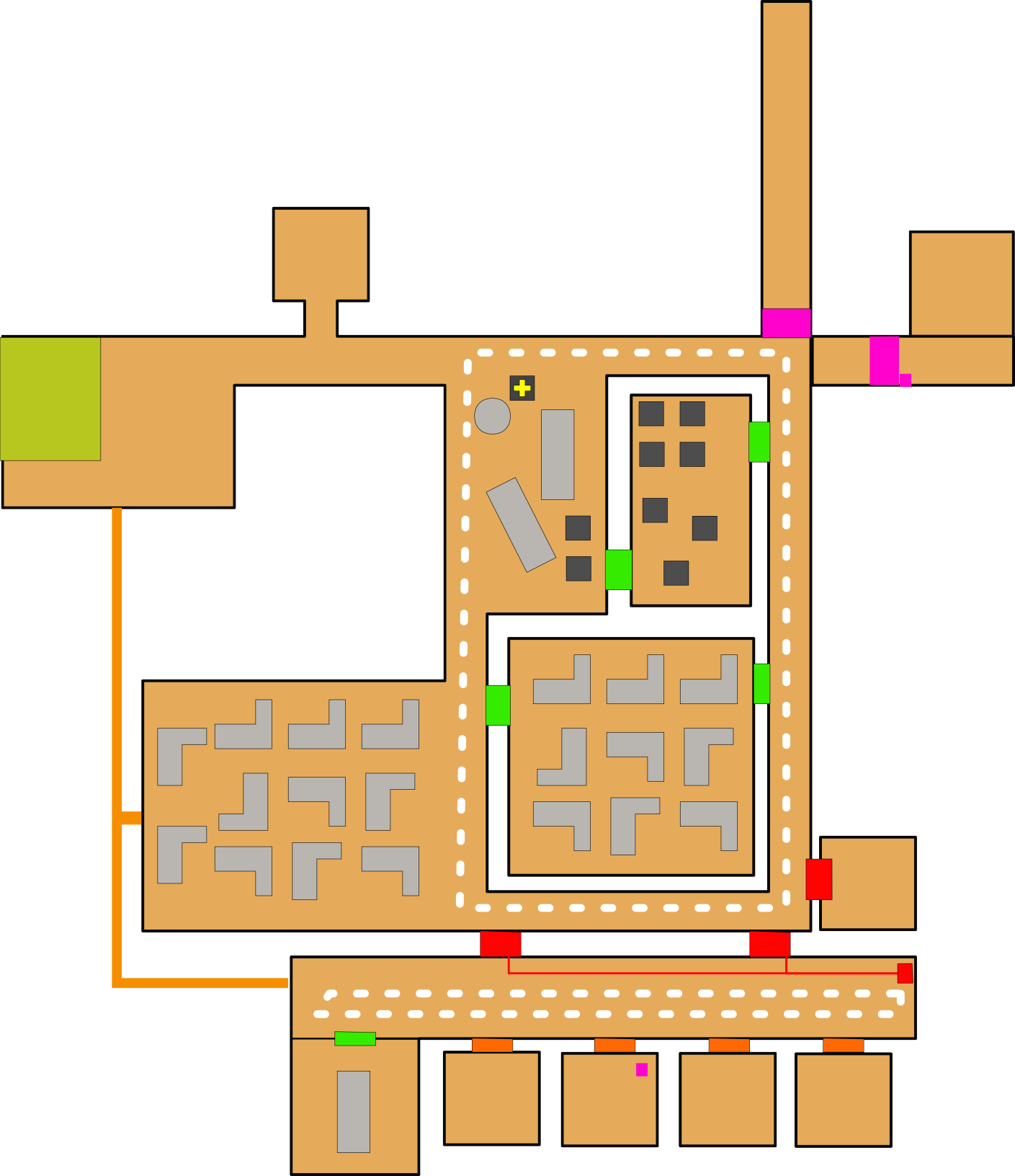

We invested early on in creating tools to speed up the level creation process; however, none of our tools were faster than simply drawing it out on paper (or in my case, Inkscape). Seeing it drawn out let me place the basis of the layout I wanted, as well as placing patrol paths and interactable object locations. It's easier to iterate when the process of creating or destroying an area is just painting some pixels. Later on these designs could be translated into the engine and whiteboxed to be play tested..

The attached image is of the fourth level in the game and the second encounter the player will have with the patrolling cyborgs. Progress in the level is spread into three acts. First, the player explores the space searching for the entrance to the C-suite offices. They can encounter the enemy's patrol path, but are given ample places to hide in the various rooms that cyborg does not actively patrol. Once they gain entrance to the C-suite they are put in a much more challenging scenario, having to avoid a cyborg in a narrow hallway with limited cover. The player can take shelter in any of the offices, but unlocking the door takes a charge from their multi-tool. Once the player finds the correct terminal to unlock the level exit, act three begins. A separate door opens, allowing a second cyborg to enter the main area timed to make it likely to spot the player if they run directly to the exit. This can present a heightened challenge as the player needs to use their knowledge of the level to find an alternate route, or it can create a high stakes chase as they dash through the cyborg's line of sight and try to get to the elevator before they're caught.

It starts with just a drawing to feel out the layout before translating it into the unreal engine

Plans change

It's impossible to know just from the first draft on paper how it will play, and this particular level had several problems pointed out by playtesters. The vents along the left edge were not fun, and the animators' time was better spent elsewhere rather than making crouching animations just for one level. Players also got stuck in the long hallway along the bottom, spending a lot of time waiting on a patrolling enemy path with nowhere to run to if they got spotted.

This required me to retool the level, providing an alternate means of entry and turning it from a line to circuit to allow the players more escape routes when trying to avoid being spotted.

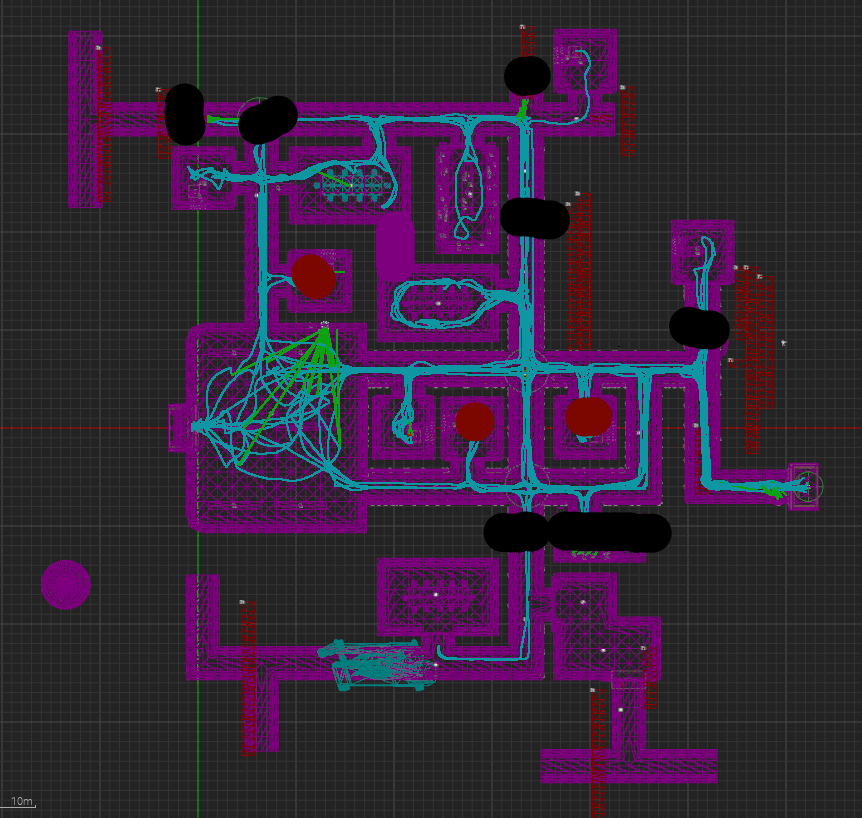

You can't get too attached to any one idea. If it doesn't test well, it has to change. Using the telemetry technology our team created, I was able to identify areas players got stuck, lost, confused, or simply never encountered, and could then make changes to more clearly direct them. In earlier drafts, the wires were tucked neatly into the environment to look aesthetically pleasing, but after seeing the data I changed them to hang down from the ceiling haphazardly to better capture the player's attention.

A screenshot of the telemetry tool our team created. The blue line represents areas the player went, the green lines represent things the player interacted with using the multi tool

Once the level has been tested, it can be handed off to the artists to give it a beauty pass, adding the lighting, textures, and prop work needed to make it shine

Mercy for Machines is a third-person survival horror game about descending into an abandoned Antarctic research base swarming with hostile cyborgs. Built in Unreal Engine 5 with a team of 16 people, including programmers, artists, designers, and audio composers/sound designers, the game was developed from August 2023 to April 2024 as a Junior year academic project.

When creating the game our core design pillars were:

You are not meant to be able to do something, but you must try.

The character is small and weak compared to the world.

You don’t belong here.

The final version we were able to deliver features five unique levels, a detailed narrative, and simple enemy AI. While I’m proud of the work that we did on the game, I do not believe that we were fully able to deliver on our initial ambitions due to a variety of factors, some within our control and others outside our control.

Pre History

Every year, the DigiPen game project classes are taught by different professors with their own goals and expectations for the class’s outcomes. In my junior year, the GAM 300 class sought to unite all disciplines onto a game project made in a commercial engine (Unity or Unreal, with most teams choosing to use Unreal), with the end goal of introducing us to the tools and methods commonly employed in the game industry. Every semester starts with a pitching process where students can present their ideas and hopefully get their fellow students to sign on; however, for a project to be greenlit, it needs to hit some minimum requirements. One of the most significant requirements is that in order to have any artists on the team, your project must have a minimum of six artists in the Bachelors of Fine Arts degree track (Abbreviated to BFA). Any less and they will not have enough people to divide the necessary workload required to meet the high expectations and learning outcomes of the course.

The game that would become Mercy for Machines started off as a pitch for a puzzle game called Sinpo (short for signal processing). The art would be created with a Cassette Futurism style and would be set in some sort of abandoned facility. I was busy pitching my own game, an homage to the Riddick games about a racoon escaping from a prison built in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, but when it became clear that I wouldn’t be able to get enough people to sign on to my project to make a viable team, I decided to disband the team early to give everyone time to find spots on other teams. The Sinpo team would have been my second choice, and thankfully they had space for me. Unbeknownst to me, they were in a similar situation to me with my pitch. While I was struggling to attract artists, they were struggling to attract tech, and ended up merging with another team that would shape a new direction for the game.

Pre production

While the art style and setting remained the same, the gameplay would pivot to instead be an over-the-shoulder survival horror game with a rogue, divine AI as an antagonist. I was very tired from being the design lead/producer of my sophomore year project, and was looking forward to stepping away from leadership in that arena. Unfortunately, when no one stepped up to take the role of producer and I was the only one with prior production experience, it was decided that I should assume that role again. I had never used the Unreal Engine before this point, so my goals going in were to use this project as a learning opportunity on how to use the engine. This would cause a lot of difficulty and conflict for me in the first semester, as oftentimes my duties as a producer managing a large multidisciplinary team would conflict with my goal to just learn how to work within the Unreal Engine. Since I was on the Bachelor of Science in Computer Science and Game Design degree track (abbreviated to CSGD), I was also expected to perform design work for the project, especially when we failed to attract any dedicated Bachelor of Arts in Game Design (Abbreviated to BAGD).

This exacerbated problems we experienced in pre-production. While I was concerned about the direction the game was taking, I wasn’t sure to what extent I could assert myself in those early brainstorming and planning meetings; I was a late arrival to the project, I didn’t have any experience in the engine, and as the producer it was expected that my role would be to be reining in creative ideas rather than supplying them. It became very clear early on that despite having enough people to fill the seats, we were far from a united team. Our creative lead was still very passionate about his failed pitch and wanted to bring as many aspects of it into this new unified team as he could. The rest of the team didn’t share his enthusiasm, and the original Sinpo group wasn’t enthused about the ideas he brought to the table. This led early creative meetings to feel more like custody battles than productive and exciting opportunities. One by one I watched people get disillusioned and check out as their ideas were shouted down. What we arrived on was a compromise that left no one happy or enthusiastic to work on the game.

The core design we’d planned used Dead Space and Metroid as emulation targets. The player would have an electric multi-tool that would perform multiple functions that all drew from the same power reserve. There would be scarce batteries to find around the levels with the player having to carefully pick the right time to use each tool, or else they could be left exposed and helpless.

One challenge when laying out the design came from the constraints placed on the art team by the instructors. We were allowed a maximum of three character meshes in the game, one of which would have to be the player character because our game was in third person. We were not allowed to use off the shelf animations, meaning every single action in the game had to be tied to a student-made animation. This would ultimately end up limiting our scope dramatically, with actions like sprinting and crouching needing to be cut because we lacked the animation budget.

Production Begins

Early on, I partnered with Andrew Roulst, a fellow CSGD that I would go on to work with in my senior project Breath of the Sky. He was our resident Unreal expert, and he helped me get up and running on the engine. Our first project was creating a system to build modular levels, something we committed to early on. It helped me figure out the blueprint system, and while it was an excellent learning exercise, I think it was ultimately detrimental. Level segment blueprints were given attachment points that could be clicked on to attach other segments. Cool as it was, in most cases it was just as fast if not faster to drag objects out of the asset tray.

The design wasn’t coming together well at all, with most design meetings devolving into hours long semantic arguments that didn’t get us any closer to agreement. One egregious instance that I recall specifically involved us going back and forth on the definition of terror and horror, and which category we wanted our game to fall into. Another point of contention was the game’s status as a horror/stealth game, and whether or not a horror game is allowed to be fun without compromising the horror.

An idea I put forth involved emulating Metroid’s systems more, giving the gun the ability to open and close doors. Players would be able to tap “fire” for a weak shot that would power up doors and stun enemies, and hold down for a charged shot that would overload and de-power doors and deal serious damage to an enemy. Enemies would flee after taking a few light stuns, but the player would be unable to deal real damage with a charge shot if the enemies caught them by surprise. A specific user story involved getting seen by an enemy, shooting a door to open it, and then using a charged shot to close the door in the enemy’s face. Ultimately, this idea was not fully adopted by the team; it was seen as too action focused and empowered the player too much.

Another idea I proposed was to have a variety of switch boxes around the level that the player would power up. These would lead with wires to various logic gates. The multi-tool could be used to power up areas remotely, but would create a sound that would attract patrolling enemies to your location and thus force more interaction with the enemies to accomplish the necessary objectives to progress. This idea was also not fully accepted because the logic gates were seen as too far from horror and stealth and would make the game into a puzzle game.

We simply couldn’t come to an agreement about what mechanics we wanted to have in our game, which was incredibly detrimental to the game’s health as a whole. Miscommunications lead to assets to be requested from the artists that would eventually be phased out when the design pivoted away from using them. Different designers would prototype their own pet mechanics without any respect for how they would integrate with the overall game’s systems. An illumination system was planned where enemies could spot the player more easily if they were in light rather than shadow and thus there would be a reason to spend your limited power to disable the lights in a room. While this feature was prototyped, it was not properly communicated to the strike team working on enemy AI, who made no use of the system.

These are all problems that a producer is supposed to help, but to be honest, I was in over my head. It was a larger team than I had ever worked with, using tools I didn’t fully understand, and a design that wasn't coming together. I’m far more accustomed to leading small teams where I have intimate knowledge of the tools in use. All through this process Andrew would be my right hand man, picking up production tasks when I didn’t get to them in time. He had a solid grasp of the engine, solid organization, and relative stability in his other classes allowing him to devote time to the project.

One of the hardest decisions as a leader is the right time to step down. It was clear that I wasn’t delivering for the team in my role as producer and Andrew would be a much better fit for the position, so I asked him to take my place when the team re-formed for the second semester.

We pushed to get a working prototype to show off for the end of the first semester. It featured three distinct rooms with switch boxes the player would need to turn on to open an elevator to escape. While it did feature all the mechanics we intended to include, they were far from a polished state and the game wasn’t really clicking. Playtesters were confused and no one felt particularly proud to show it off.

One semester down, one left to turn it around

During the winter break, we got a message from our creative lead. He was dropping out of the school and wished us all the best. We needed to find someone to take his place, and since I was no longer in the role of producer we decided that I would take up the role.

Coming back to the project with fresh eyes, I took stock of what we had and tried to re-orient the game into something more cohesive. While we had more cohesion now that the design team was smaller and more unified in what we wanted the game to be, we were also more limited than ever before. We had only the assets we’d already requested from the artists with very little wiggle room to request extra work, and we had only one further semester. We couldn’t reboot the project and start from scratch; we had to work with what we had.

The multi-tool was reduced dramatically in scope. It could turn on switch boxes and stun enemies, but any of the other planned features were scrapped. The resource scarcity of the game had to be dialed back dramatically, we just didn’t have the design power to make it work, and repeated playtests showed players getting stuck and frustrated when they ran out of power, so plentiful recharge stations had to be added to all levels.

There would be one enemy mesh that could be divided into a blind variant that could hear the player and a deaf variant that could see the player. There would be a final boss at the end involving a spotlight which would combine both behaviors, letting the boss spot for the blind enemies.

Closing doors on enemies had to be cut. We could not find an elegant way for the player to trigger the interaction, and making the enemies not get stuck in the doors was something our tech team couldn’t figure out in a reasonable amount of time.

I began to have very serious struggles with my mental health in that semester. While the game was more cohesive, it still wasn’t fun. I wasn’t the only one struggling. One of our programmers only committed three things to the repository and never showed up to any labs or meetings, so we had to invoke the process laid out by the professors to fire him. Another of our artists did the same thing, and another left the project as well. Our artists were overworked and were not able to get additional art talent to join the team. It was becoming hell to work on the project.

Late into the first semester, a computer terminal was added to the repository, and one of our programmers decided to give it a functional command line interface as an after hours project. The terminal was simultaneously everything that was great and everything that was wrong with the game.

The terminal was cool, polished, and playtesters loved it. As we got more and more positive feedback about the terminal, I made the case to the team that we should incorporate it more into the game as a core feature and not just an easter egg. The terminal helped get everyone on board and enthusiastic. It allowed members of the original Sinpo team to have an alternate way to tell the story they wanted without cutscenes that were now off the table with the diminished artist count. I love writing, and while the game was not fun for me to play or work on, I was able to show up to work excited to write the game’s narrative and find creative ways to tell environmental stories with the limited selection of art assets we had.

For all the good things about the terminal, it was also an indicator of our team’s core dysfunctions. The terminal wasn’t in the game design document, it wasn’t something we’d planned on, it was a feature that one programmer prototyped on a whim that made it into the main repo. While it ended up being good for the game, it spoke to our lack of clarity, direction, and communication.

I’m a generalist, I go where I’m needed for the team and do what I can to support it. While I was slowly learning to use Unreal, I got incredibly demoralized with how often I would need to ask Andrew for help on using basic features of the engine. As many good ideas and designs that I had for the character controller, it was clear that as a programmer I couldn’t keep up with the team assigned to work on that feature. I was given a level to work on, and while I do not feel a particular passion for level design, I was qualified to do the work and threw myself into it to the best of my ability.

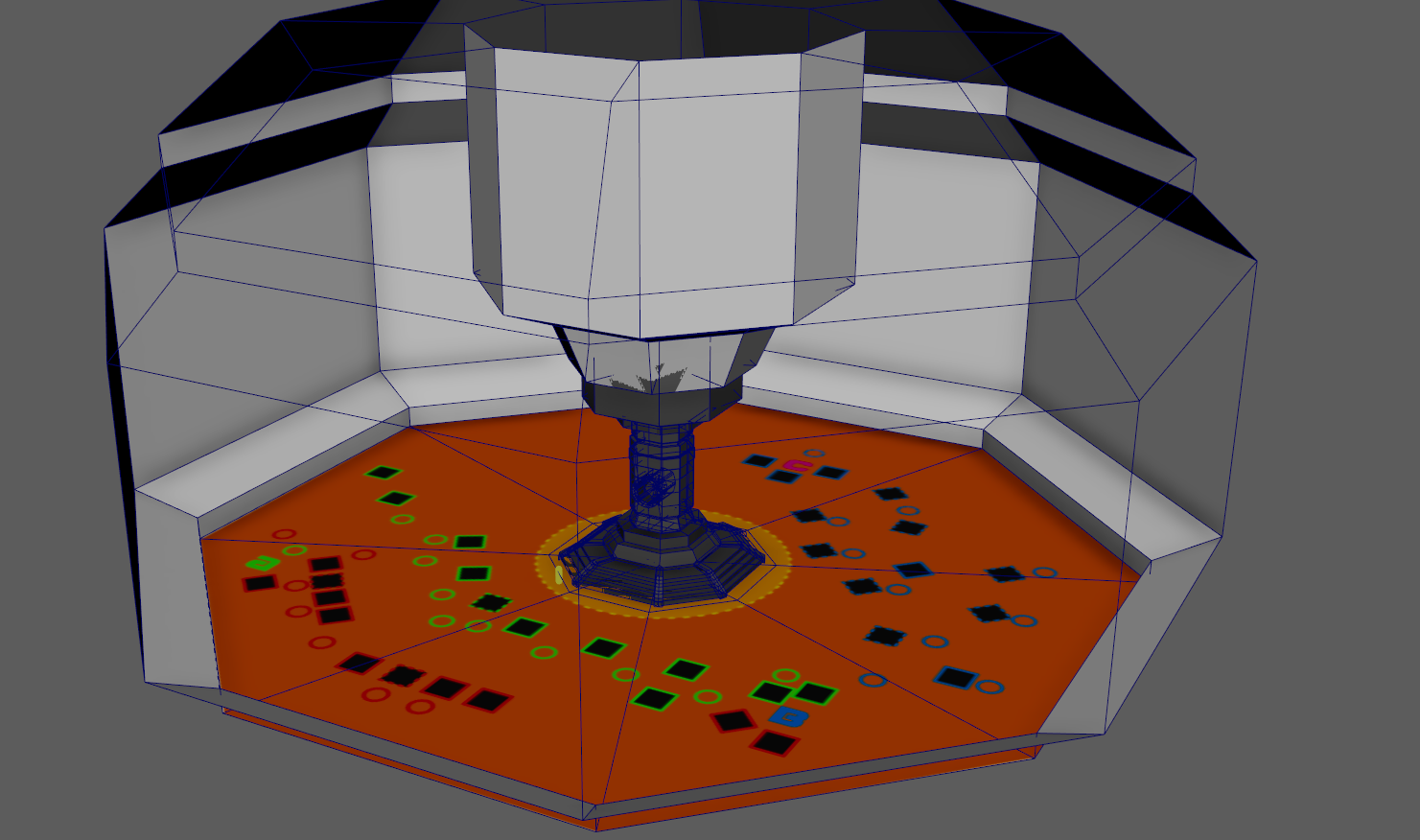

What I really wanted to work on was the boss fight. I saw it as the chance to make the game fun. I worked closely with our level artist to build out a specific arena for it, a massive open chamber with a spotlight in the center. Capacitors would raise and lower as the eye sweeps around the room. The player has to play red-light-green-light across three stages to avoid the light and get to terminals to eventually shut the AI down.

While I wrote what I thought was a good spec for the fight, I wasn’t able to implement it myself and I needed to rely on the help of the tech team. I’m very embarrassed to admit that the first playable version of the boss made it into the game on the final day before submission. While it worked, it wasn’t ever playtested. I wanted it to be the crowning achievement I could show off in my portfolio; instead it ended up being the dark stain that I’m most embarrassed about.

Endings and reflections

Mercy for Machines was not greenlit for an extra semester of work in the GAM 375 class. Eventually the class ended and we submitted it. I think it was an excellent learning exercise, I picked up a lot of skills in the process, but I don’t think it ended up being a very good game. A lot of the game’s faults rest on my shoulders: I wasn’t doing well as a producer and took too long to pass the role off to someone more qualified. The design ended up being lackluster, and if I had been a stronger advocate for my ideas earlier in the project we may have made something more playable. There’s nothing I could have done to prevent four people from leaving the project, and a certain degree of the game’s problems can be attributed to all of us trying to do so much with so few people, but I know for a fact I could have done better. I did the best that I could with the hand I was dealt, and learned. As someone who worked on the game it’s difficult for me to separate what is from what could have been.

Taking a more objective route, there is a lot to be proud of. The game has a cohesive narrative, it has a decent playtime for a student game with multiple varied levels, and is optimized enough to hit 60 fps on low-end hardware (something few two-semester student games can reach). It’s about the process and the lessons learned more than the final product. As a creative I’m very harsh on my own work, and as it’s likely been made clear through this post mortem, I feel like I could have done so much better. That’s one of my greatest weaknesses: I focus on the negative aspects. It’s so much easier for me to fixate on flaws than for me to celebrate victories. It was an academic project, and all of us who stuck with it passed. We learned a lot, and I made friends who I stay in contact with today through that project. If I could do it all again, sure, there would be so much I would change, but I would still do it again. I think it was worth it to learn all the lessons that I did.